This coming Sunday, February 1, is my “name day,” the feast of Saints Perpetua and Felicity. Though this group of martyrs also includes four men, it is for the two women that the day is named, with St. Perpetua in the lead. This awarding of honor is with good reason; Perpetua was an extraordinary woman. Her story is just one among thousands, but it is so marked by drama and courage that it offers a particularly good example of why we cherish our saints.

Perpetua was twenty-two years old, married to a man of good social position, and the mother of a baby boy. She was arrested during the persecution of 203 A.D. in the city of Carthage in North Africa, now Libya. Others imprisoned with her included Saturninus and Secundus, the slave Revocatus, and another slave, Felicity, who was pregnant. Their catechist, Saturus, was not with them when they were arrested, but he hurried to the prison and joined them, declaring himself a Christian.

The reason this martyrdom has particular historical value is because Perpetua wrote it herself, keeping a journal up until the day before her death. The account was so esteemed by the African churches that St. Augustine (a fellow North African), needed to warn the faithful not to place it on the same level as Scripture.

The Church Father Tertullian (AD 155-220), also of Carthage, was no doubt there when these things happened. He wrote up their story to preserve it, sounding a little defensive:

If ancient illustrations of faith which both testify to God’s grace and tend to man’s edification are collected in writing, … why should new instances not also be collected, … if only on the ground that these modern examples will one day be ancient?

All of Perpetua’s family, except her father, were Christians. She was his favorite, and he no doubt feared (with good reason) that her profession of faith would mean her death. The plight of this old man adds much pathos as it weaves through his daughter’s story.

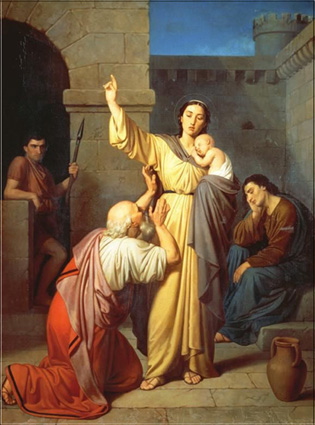

When Perpetua was first arrested, her father came to the prison in great distress, crying out, “Daughter, pity my white hairs! Pity your father if I am worthy to be called father by you, if I have preferred you to your brothers. Look on your mother, look upon your son who cannot live after you are gone. Lay aside your pride, do not ruin us all.” Perpetua says he kissed her hands and cast himself at her feet, “and with tears called me by the name, not of ‘daughter,’ but of ‘lady.’ And I grieved for my father’s sake, because he alone of all my kindred would not have joy at my martyrdom.”

Soon after that, the prisoners were summoned to be examined by Hilarian, the procurator. A great crowd gathered to hear the judgment, and from the midst of it stepped Perpetua’s father, carrying her baby. “Drawing me down from the step he besought me, ‘Have pity on your child.’ Hilarian joined with my father and said, ‘Spare your father’s white hairs: spare the tender years of your child.’” Yet Perpetua still refused to offer a sacrifice to the emperors, and declared she was a Christian, making strong arguments for the faith.

Her father pleaded with her so strenuously that Hilarian commanded the old man be beaten and dragged away. “This I felt as much as if I myself had been struck, so greatly did I grieve to see my father thus treated in his old age.”

Sentence was passed: the prisoners would be slain by wild beasts, as part of the entertainment for the birthday celebration of the emperor’s son. “Joyfully we returned to our prison,” Perpetua writes. She asked for her baby to be brought to her to nurse it, but now her father refused to surrender the child. “And God so ordered it that the child no longer required to suckle, nor did the milk in my breasts distress me.”

Perpetua awaited martyrdom serenely, and recorded several dreams and visions that reassured her. He fellow-prisoner Saturus wrote down a vision as well. He and the other prisoners were brought by angels to a garden, where they met friends who had been martyred shortly before. From there they came to a throne-room, where a majestic figure sat surrounded by elders singing “Holy, holy, holy.” Saturus writes, “we kissed Him, and He passed His hand over our faces” (as if brushing away their tears, as in Revelation 7:17). They exchanged the kiss of peace, “and the elders said to us, ‘Go and play.’”

In his dream Saturus told Perpetua, “You have all you desired,” and she responded, “Thanks be to God that as I was merry in the flesh, so am I merrier here.”

Felicity was now eight months pregnant, and began to fear that she would not be able to suffer with her companions, because the Romans would not execute a pregnant woman. Felicity might be held back, and be executed later with criminals. But they all joined in prayer, and Felicity immediately went into labor, giving birth to a daughter. The child was adopted by a couple in their church.

When Felicity was in labor she cried out in pain, and the guards mocked her, saying it was nothing compared to what she’d endure when the animals tore her apart. Felicity responded, “Now I bear my own pain, but on that day another will bear the suffering in me.”

As the time approached for their martyrdom, Perpetua concluded her manuscript: “This is what I have written until a few days before the exhibition. What will come to pass at the exhibition itself, another must write.”

Finally the day of the games arrived, and Perpetua walked into the ampitheatre singing a triumphal hymn, “abashing the gaze of all with the high spirit in her eyes.” Tertullian writes, “The populace shuddered as they saw one young woman of delicate frame, and another with breasts still dripping milk from her recent childbirth.” The guards tried to force the prisoners to wear the robes of worshipers of Saturn and Ceres, but Perpetua protested so forcefully that they backed down.

The men in the company were swiftly killed by leopards and bears. Felicity and Perpetua were exposed to an enraged cow, which tossed them both but did not kill them. Perpetua sat up, pinned her hair, then went over to lift Felicity to her feet. She asked when they would be taken to face the wild beasts. She didn’t believe that it had already taken place until she saw her own torn clothing.

The crowd once again clamored to see the two women killed. The patrician woman and the slave woman exchanged the kiss of peace, then were beheaded. Perpetua’s executioner was nervous and, at the first blow, only wounded her so that she cried out in pain. The second and fatal blow she herself guided to her throat. Tertullian concludes, “Perhaps so great a woman…could not have been slain otherwise, except that she willed it.”

We live in such a comfortable age that we may worry if we’d be able to be so heroic, if such trials should come again. But that kind of courage must always be a gift of God, a miraculous gift he could grant us as well, undeserving as we are. But it’s the style with which Perpetua did all this that we couldn’t match. She was bold, a powerful debater, indomitable, with “high spirit in her eyes.” Yet she was tender as well: a nursing mother, a loving daughter, and “merry.” Perhaps “so great a woman” could only be formed by so great a faith, and only revealed by so great a challenge. How many others like her, I wonder, are lost to history. But never lost to God, who was with them through their trials, saints we will one day meet among the company that Saturus envisioned around the throne.

Perpetua is an astonishing saint, but she is not my patron saint. I chose the more humble Felicity, who suffered as much as Perpetua did, but didn’t have the wit or education to put it into fine prose. Her voicelessness is an example to me, a reminder of all the voiceless and forgotten saints who surround the throne, many whose names are forgotten, known only to God. That crowd is so broad and includes so many types of faithful, both humble and great, that it gives me hope that I might stand there one day too.